Using proxemics, focus and opposition to explore Macbeth’s state of mind.

I really like this task sequence because it’s so simple and it’s really easy for the students to see the connection between what they are doing and the meaning that it creates for the audience. The sequence works both in the classroom and online (as long as students have a reasonable amount of space to “walk the text”).

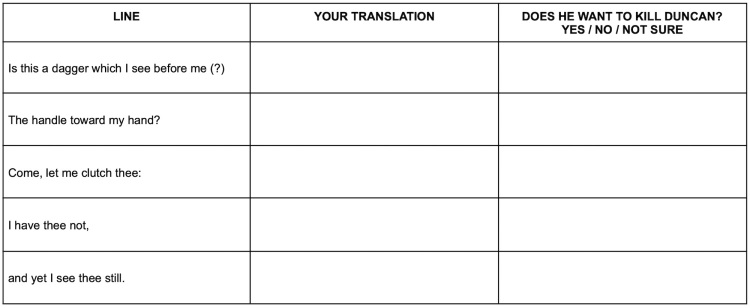

This is adapted from a task in The RSC Shakespeare Toolkit for Teachers, but builds on it quite considerably. Working with a wide mix of language abilities, I use an edited version of the soliloquy, and, Pre-Covid, I would have gone through this line by line, asking the students to make notes on their copy, to ensure they understood everything. Their homework task would have been to highlight each chunk of the soliloquy to indicate whether they thought the words indicated that Macbeth

- Wants to kill King Duncan.

- Doesn’t want to kill Duncan.

- Isn’t sure if he should kill Duncan.

Working online forced me to change all that, and I am pleased that the outcome is a change for the better that can be carried back into the classroom. To make sure the students stay actively engaged throughout the process I used a combination of a table created in Google Docs on Google Classroom and a set of slides enhanced with Peardeck. You can download a pdf copy of the table here.

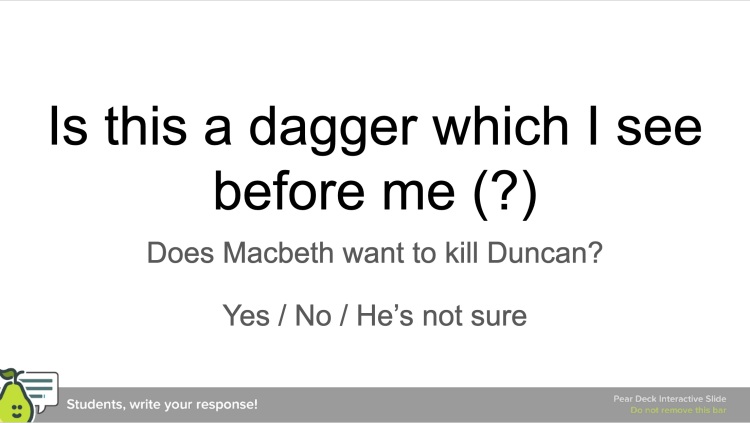

| Peardeck can be used as an add-on for Google Slides. It allows students to respond to questions on the slide in real time, and enables the teacher to see all responses. These can then be shared anonymously with the class, or viewed privately by the teacher with student names attached. It’s a brilliant whole-class response system for formative assessment, and easily makes active learning a part of slide presentations. |

Task 1 – Inner Monologue

By the time we get to this task, my students are already familiar with Inner Monologue. Here we reduce it down to a simple series of “I want to kill Duncan”, “I don’t want to kill Duncan”, “I’m not sure if I want to kill Duncan” statements.

Step 1

After reading the whole soliloquy aloud, work through it one “chunk” at a time. A “chunk” might be a complete sentence, or just a single clause. Translate the first chunk, and allow students time to write their own translation in the “Your Translation” column of the table. They can write in English or their home language.

Step 2

After translating the first “chunk”, switch to Peardeck. I made a slide for each chunk, and enabled the text response option. Ask students to write on the slide whether they think these words suggest that “Yes” Macbeth wants to kill Duncan, “No” he doesn’t, or he’s “Not Sure”. Encourage them to give a reason for their choice.

You will probably need to ask students to focus just on the words (and punctuation), and to ignore for the time being the knowledge they already have about the play. Students frequently write about the influence of Lady Macbeth or the Witches, or about Macbeth’s character traits. Praise them for having and applying this knowledge, but model answers for this first chunk that focus only on the words that he is saying in that moment:

Yes, because he can see the dagger and the dagger symbolises the murder of Duncan.

No, because although he can see the dagger he asks himself if it’s actually there, which suggests that he doesn’t believe it is real.

Not sure, because he can see the dagger, but the question mark shows that he’s not sure if it’s real or not.

Step 3

Show and read through all student responses, then ask students to fill in their choice in the final column of the table. Emphasise that they can change their minds from what they wrote on Peardeck if someone else’s reason has persuaded them otherwise.

Step 4

Continue through the other chunks.

I really like that this sequence reduces the cognitive load for all students, but especialy for those with emerging English, and also allows them to see multiple model answers from their peers, and how their work compares to their peers, without any sort of formal ranking or comparison. As a teacher, of course, you are highlighting strong points in their responses as you read through, as well as suggesting improvements to weaker answers. If you’re referring to “this answer” as you talk through them, it’s clear that you’re commenting on the response, not on the student who wrote it.

Task 2 – Proxemics

To reduce cognitive load again, I will be reading the soliloquy for all tasks, so students can focus on the movement.

In this task, as I read, students will move forwards when I am reading a section that they have marked as “Yes”, backwards on “No” and pace from side to side for “Not sure” (The RSC Toolkit version has them stand still for “not sure”, but for this variation of the task, continuous movement is more effective). When they are going backwards they should be backing away from their camera (if they are online), not turning to walk away.

(It’s important to use the words forwards and backwards at this point to highlight the progression that’s made in the next task.)

Emphasise that you want then to move continuously (Frequent Student Misunderstanding: I just take one step for each line), so they should make sure that they have enough space, and move at a pace that won’t lead to them running up against walls or furniture before the end of the soliloquy.

You’ll probably need to go through this three or four times – give them the opportunity to change their starting position if they need to, and to check any of their “Macbeth’s state of mind” choices that they might have forgotten.

Once the task is over, ask them what an audience could tell about the character just from watching this movement, even if they didn’t know the story of Macbeth and couldn’t hear the soliloquy. Guide answers towards the idea that they would see a character being pulled in different directions by their thoughts or that it’s someone whose thoughts are jumping all over the place.

You can also suggest that the proxemics at work here turn the floor into a map of Macbeth’s mind as he moves from thought to thought, which each separate thought located in a different location. This way of interpreting the movement is based on ideas from some of the exercises in Barbara Houseman’s Tackling Text [and subtext]: A step-by-step guide for actors.

Task 3 – Focus

Repeat the walking exercise, with the teacher reading the soliloquy, but this time ask the students to focus on a point on the wall in front of them (behind their camera if they are online), about midway between the top of their head and the ceiling. They should maintain their focus on this single point, which, of course, represents the ghostly dagger that Macbeth sees, throughout the soliloquy, whichever direction they are walking in.

Again you are likely to need to run this two or three times, to make sure that students maintain the focus. It is most likely to disappear during the side-to-side pacing (Frequent Student Misunderstanding: I need to keep looking straight ahead of me), so it’s a good idea to model walking in all directions while keeping that focus on the single point.

Once it’s working, ask them whether backwards and forwards are still the right words to describe the movement when we add in this focus. Hopefully, at least one of them will suggest that towards and away from are now more appropriate.

Ask how the audience’s understanding of the movements has changed now that we have added focus to them. Guide the answers towards the idea that now, rather than simply having confused thoughts jumping from idea to idea, Macbeth now seems to have a target, goal or objective, and the focus shows him making a decision whether or not to go through with it. We see him moving closer to doing it, and then retreating from taking action. We get a much more precise image of his inner world.

Task 4 – Opposition

Opposition is an under-taught technique that may be unfamiliar (at least by name) to some Drama teachers. I first came across it in Eugenio Barba and Nicola Savarese’s Dictionary of Theatre Anthropology. For me, it’s one of the most important (and simplest) techniques our students can use to really raise the power of their performances.

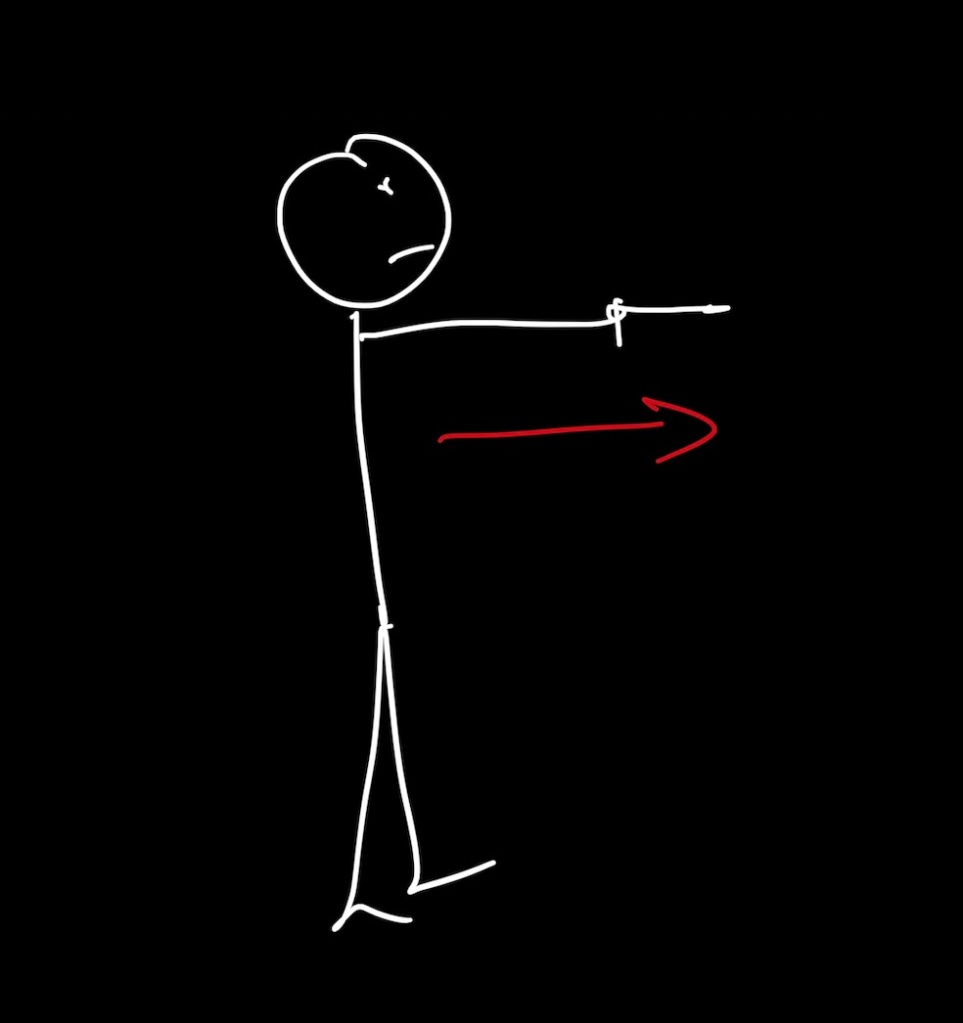

Essentially, it’s kind of like Newton’s Third Law of Motion (so, room for a bit of cross-curricular science, maybe): “For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction”. If we take the direction of force, tension, energy or focus from a performer’s pose or movement…

…and apply energy, tension, gesture, focus or movement in the opposite direction, the image become more dynamic, powerful, controllable, and generally stronger.

The technique is one that we see in everything from Melodrama to Balinese Dance to Superhero Comics. In cartoons, when Scooby Doo leans backwards and winds up his legs before running forwards, that’s opposition. I suspect that musicians use it to balance the downward force of their fingers (I’m imagining a pianist, here) with an upward force to control the lightness of their touch on the keys. It’s also there in painting and sculpture.

Step 1

Ask students to stretch out their right arm to try to touch the wall (if they can touch the wall, tell them to move further away from it) – “stretch till it hurts”. Then relax. Repeat with the left arm. Relax. Now with both arms. That feeling of being pulled in two directions at once is opposition.

Step 2

Now ask them to try as hard as they can to touch the wall in front of them with their nose, but without bending too much at the waist. Relax. Now try to touch the wall behind you with your butt, again without bending too much. Relax. Now both at the same time. That feeling of being pushed in two directions is opposition.

Step 3

Now try applying opposition to walking. As you walk forwards, feel yourself being pulled or pushed backwards, as if there’s really strong elastic attached to the wall behind you and tied around your waist, or someone in front of you is pushing back against your shoulders, or you’re trying to walk in a chest-deep swimming pool.

If any struggle visualising that, tell them to walk with their weight on the front half of their foot. Push backwards with the foot that’s in front, and forward with the foot that’s behind. Switch over once the back foot has stepped forward.

Try the same thing walking backwards.

Step 4

Now have the students walk the soliloquy again, while you read, maintaining the focus from Task 3, and now applying opposition to their towards and away from walking.

When they are on a “not sure” line, this time, instead of pacing from side to side, they should stand still and feel themselves being pulled from left and right, or pushed as if the walls are closing in and they’re trying to push them apart. (Arms raised at a roughly 45 degree angle from the body is a good position for this).

Step 5

Ask how the audience’s reading of the movements have changed now that we have added opposition and focus to the movement. With focus added we saw Macbeth shifting between “Yes” and “No”. Now that we have added opposition, it becomes much more nuanced, and we see his inner conflict much more clearly – his thoughts are telling him “Kill Duncan” and “Don’t Kill Duncan” at the same time.

When we add opposition, instead of seeing 100% “I’m going to kill him” changing to 100% “I’m not going to kill him”, we see 60% “yes” and 40% “no” changing to 20% “yes” and 80% “no” (have the students add percentage ratios to the table and you’ve done your cross-curricular maths for the week). He’s not just shifting from one point of view to another, he’s being pulled in both directions at once. The character has suddenly become much more three-dimensional, with a much more vivid inner life, and the students’ performances will really hold the audience’s attention.

Extension Task: Learn the soliloquy and use these techniques to create a performance that uses movement in and around the whole space, rather than just in a straight line backwards and forwards.

In my next post I’ll expand this sequence further, showing how, once we get out of current social distancing restrictions, we can use techniques from the work of Frantic Assembly to explore Macbeth’s inner conflict.